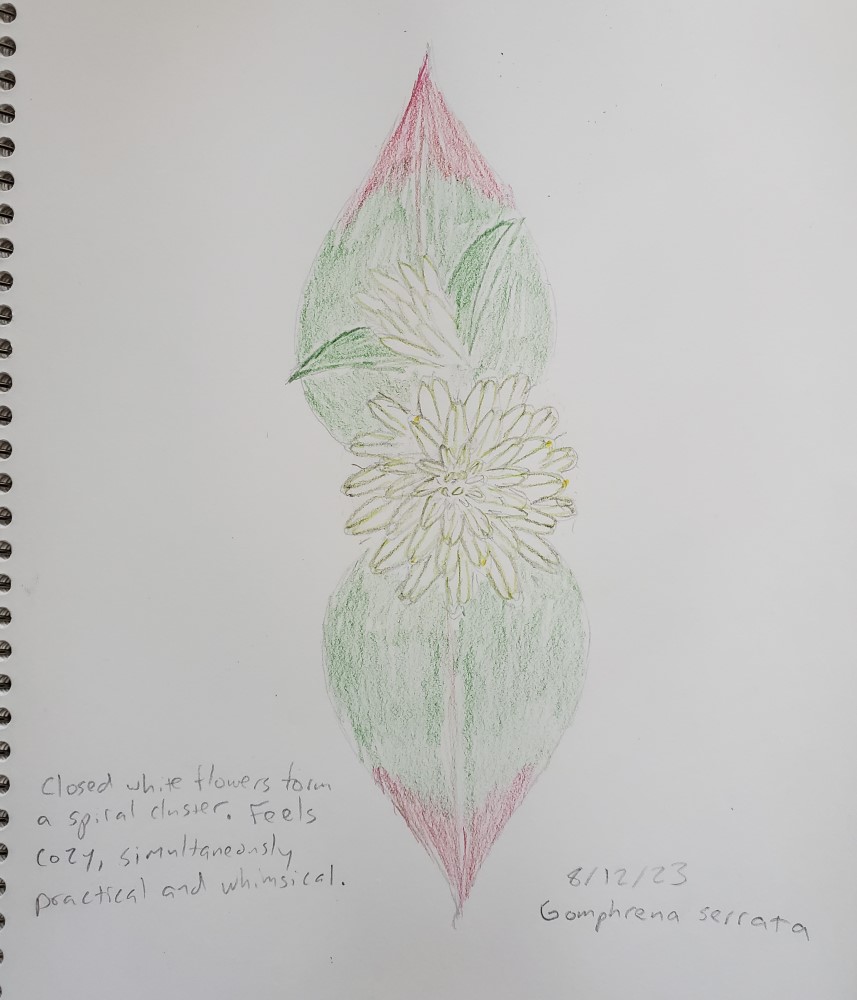

I found this flower growing in my backyard, and was drawn to its clusters of flowers arranged in a spiral, the same aesthetic I suppose that is making succulents so popular right now. I identified it, and a few days later satisfied my creative side by sitting in the hot sun drawing a picture of it until a fire ant crawled up my shorts. I figured I would do some research on it after. Maybe this would be a short post, since not every plant is a winner in terms of having lots of interesting factoids about it. Oh boy.

Little white flower, big scary name

Gomphrena serrata, with common names “prostrate globe amaranth” and “arrasa con todo” is native to Central America, and may or may not be native to Florida (Ventosa-Febles 2017). Its Spanish name means… “destroys everything”. Huh. A quick Google search for “arrasa con todo” yields a wide variety of metaphysical products, many with pictures of tornadoes or dragons on them. They seem mostly marketed to dispel curses and negative energies. Between this and the pokeweed, I have to admit I had a few minutes of panic wondering why I was finding myself drawn to plants that are used for breaking curses. But then I took a closer look at the various “arrasa con todo” products. Some of them are herbal baths or incense, but from the pictures I’m not convinced they contain Gomphrena serrata. I posted a product question to the website of one of the more reputable-looking sellers of these herbal baths, stating my interest and asking which species were in the mix, but never received a reply. I borrowed a copy of Dictionary of Plant Names (Coombes 2002) from my local library but didn’t find an answer in there either. My panic turned into obsession. Why does this plant have this name?

Jim Conrad’s newsletter article about this plant (Conrad 2022) notes that in the Spanish literature it is not called “arrasa con todo” but has various other names like “amor seco” (dry love). This isn’t the first time I have seen incorrect common names listed across different languages. The grass Miscanthus sinensis is native to East Asia and a common ornamental in temperate regions of Europe and North America. Despite its popularity, it really doesn’t have a common name in English. But one of the oldest varieties, ‘Zebrinus’, is variegated with green and white stripes, so that specific variety is sometimes sold under the name “Zebra grass”. Thus the Japanese common name “susuki” got paired with “Zebra grass” in some Japanese-to-English dictionaries. In two instances, a map of the city of Sapporo, and in the mobile game Neko Atsume, have I seen the term “Zebra grass” used to refer to Miscanthus sinensis even though that’s not actually a common English name for the species.

Here’s my hypothesis of why Gomphrena serrata is listed as having the common name “arrasa con todo”. An American botanist was visiting Central America to document the plants there. They were at a market and saw some dried G. serrata hanging in a vendor’s stall and asked “what is this called?”. The vendor, hoping to make a quick buck off a tourist, said “arrasa con todo!”, describing the plant as a magical cure-all. The botanist didn’t quite put two and two together, and simply jotted down “arrasa con todo”. The name propagated through the botanical literature and we still have it. But that’s just my guess, so if you have any further insight, dear reader, please .

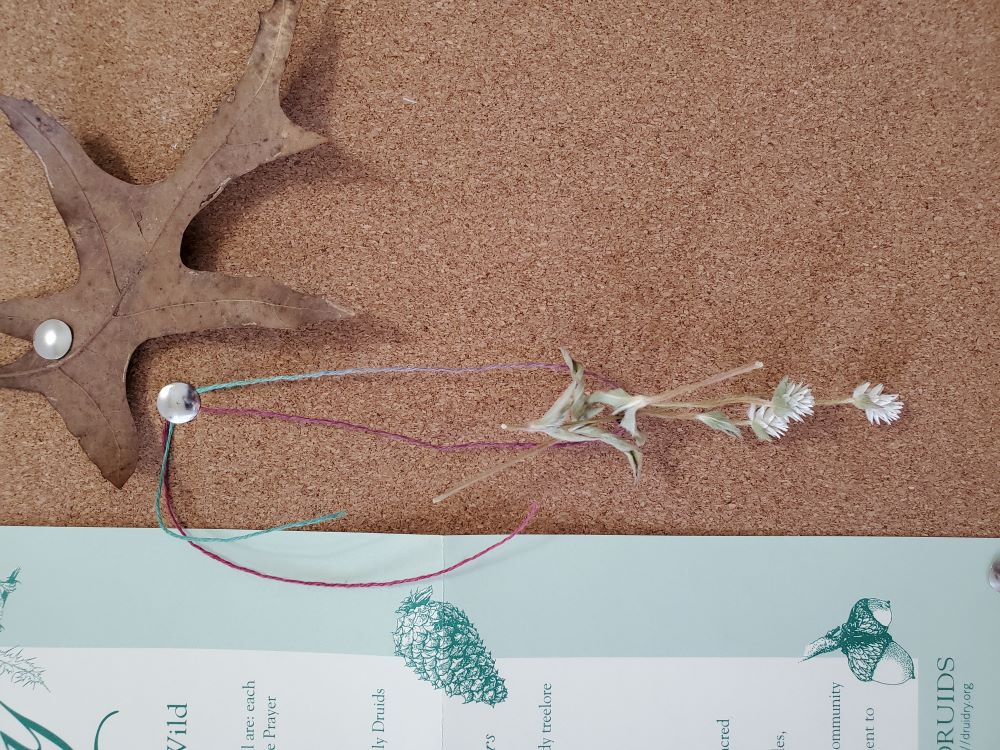

What about other species in the genus Gomphrena? Some, including G. globosa and G. haageana, are popular ornamental plants, being more upright and colorful that G. serrata (Chadwick 2017). This genus is broadly referred to as “globe amaranths”. Because the inflorescences retain their shape when dried, globe amaranths traditionally represent an unbreakable bond of love between two people (A to Z Flowers n.d.; FoliageFriend n.d.). I found one website that says the flowers are used in some cultures for protection against evil spirits, but of course it does not say what cultures or offer any citation (FoliageFriend n.d.). Arg. Well, I’m a working mom, but maybe one of these days I can use Mommy’s Precious Sanity Time to drive up to Gainesville to camp out in the UF library trying to solve this and other mysteries.

In the meantime… can’t hurt to keep some around.

Medicinal uses

Although G. serrata is native to Central America, if I search for it on Google Scholar most of what I find is research on its medicinal properties coming out of India, where it is introduced and naturalized. For example it has shown some promise for treating epliepsy (Joji et al. 2018), protecting the liver from toxins (Vani, Rahaman, and Rani 2019), and having broad antioxidant properties (Nandini et al. 2020). One group even used extract from G. serrata to synthesize silver nanoparticles from silver nitrate (Cherukuri and Kammela 2022). Gomphrena species have been traditionally used to treat inflammation, infection, bleeding, high blood pressure, cough, malaria, cancer, and diabetes (Chadwick 2017; Tarnam, Ilyas, and Begum 2014). In Mexico, G. serrata has been used for stomach problems, to “purify the blood” and cleanse away fright (Conrad 2022).

Taxonomy

Remember that the taxonomic ranks are in this order: Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species. A genus will be italicized and capitalized, e.g. Gomphrena. A species will be italicized and in lower-case, e.g. serrata. A family will be capitalized, not italicized, and will end in “ceae”, e.g. Amaranthaceae. Higher ranks are also capitalized but not italicized, e.g. Caryophyalles or Eudicots.

Once evolution became accepted among botanists, and DNA sequencing resolved the relationships among plants more and more, several unnamed ranks were added between Kingdom and Class. For example, Angiosperms are flowering plants, and Eudicots are flowering plants that have two seedling leaves, branching veins in their leaves, and a predetermined number of floral organs.

Gomphrena is in the Amaranthaceae, AKA the amaranth family, which is within the Eudicot clade. So what’s up with the flowers? Members of the amaranth family have tiny flowers that are enclosed in three bracts. A bract is a modified leaf that grows at the base of a flower, and not all plants have bracts. What looks like a spiral of G. serrata petals is actually an inflorescence, or group of flowers, and mostly you can just see the white bracts that enclose each flower (in other Gomphrena species, the bracts may be red or purple). On some of the flowers, a little yellow is visible where the stamens poke through.

If you’re following on from the pokeweed post, I’ll point out that while Phytolacca is not in the amaranth family, they are both in the Caryophyllales order, along with pinks, carnations, cacti, and some carnivorous plants. Members of the amaranth family produce betalain pigment, like pokeweed does.

This was a great excuse for me to get to know the amaranth family a little better. I have known for a long time that it was important, but never really learned to identify it. (My training is in genetics, and I have had to pick up all of my botany on the side.) Plant families are not defined by how many millions of years ago they began diverging (although a family must contain all plants derived from a single common ancestor) but rather by how recognizable they are to the average person. Once you get to know a plant really well, other plants in the same family will pop out at you and seem familiar.

For example, here is some snakecotton (Froelichia floridana) growing along a sandy, scrubby trail where I like to walk. This is also in the amaranth family. On some of these flowers you can see a little red spot at the tip where the reproductive organs are poking out.

And here is some Celosia plumosa that I bought at the hardware store as fall cover for my vegetable garden. Just look at these fuzzy little muppets! Don’t they look like they are flowering in some sort of fractal pattern? But it’s an illusion. Both the inflorescences and the flowers themselves are cone-shaped with a similar angle to them, and the bracts are so fuzzy that it is hard to tell the difference between a bract and the hair on a bract. However, although the inflorescences can branch endlessly, once you get to the level of the flower there is a fixed number of organs and that’s it. That’s the rule for Eudicots and Monocots. Anyway this species is also in the amaranth family.

Then there are the edible species in the amaranth family. Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) is in the amaranth family, as is spinach (Spinacia oleracea) and beet (Beta vulgaris). Then there’s amaranth itself, which refers to the Amaranthus genus, with pigweed being another common name. Many farmers consider amaranth to be a terrible noxious weed, especially given that it has evolved herbicide resistance (Bomgardner 2019). I am sure that tremendous amounts of money and carbon have gone into efforts to get rid of it. However, the seeds, shoots, and leaves are edible and grown for food. Amaranth is a traditional Native American crop, especially in Mesoamerica. In both the 16th century Spanish invasion and the 20th century Guatemalan civil war, amaranth was outlawed in an effort to stamp out indigenous spiritual practices, and there are inspiring stories of women hiding jars of seeds in order to preserve their traditions and their food supply (Nowell 2021). Both amaranth and quinoa are called “pseudocereals”, because true cereals like rice and wheat belong to the grass family. Unlike true cereals, amaranth and quinoa have complete protein, which make them a very healthy addition to a vegetarian or vegan diet. There are two chapters on members of the amaranth family in Stalking the Wild Asparagus, on Chenopodium album and Amaranthus retroflexus, respectively, with recommendations for using both as a potherb and grain (Gibbons 1962). Esteemed druid Dana O’Driscoll has a blog post about her experiences growing amaranth (O’Driscoll 2012). I think I would like to try it in my garden next year. It sounds like a very drought-tolerant and fast-growing crop, and I’m all about working with nature rather than fighting against it when I garden.

These plants have sparked my imagination, and I find myself picturing two cousins, and extrovert and an introvert. Amaranthus, with its deep red bracts and bountiful grain production, is a symbol of the harvest time, and all the community-based ritual and tradition that comes with it. Gomphrena serrata, laying low in prairies and forest clearings, its inflorescences like little white moons, was quietly gathered and used in someone’s magical practice, and the only hint we have is the Spanish-but-not-used-in-Spanish common name of “arrasa con todo”.