We have been in our current house less then a year, and have gotten to watch the back half of our backyard re-wild itself. Tragically we can see from Google maps that there used to be some sand pines there, and I would guess that it was cleared recently since there are no signs of mowing and yet lots of scrub and tall grasses are quickly growing in. A saw palmetto, clearly regrowing from buried material, looked almost like the bleached plastic handle of a toy poking out of the sand back in March, and now a leaf has finally forced its way out. Perhaps the previous owners were worried about damage to the house from falling trees in a hurricane, despite the large buffer of lawn between the trees and the house. A few sand pine seedlings came up this spring and I put stakes next to them so we would be sure not to trample them.

A broad-leafed herbaceous plant with big leaves and thick stems started growing this spring, and eventually got taller than the dogwood my husband had planted nearby. Once I got it into my head to start this blog, I was looking around for plants that I might want to write about, and noticed that this one had big, juicy berries growing on bright, bright fuchsia racemes attached to stems of a similar color. Not recognizing what family it was in, I used a plant identification app and found that it was pokeweed, Phytolacca americana. It turns out this plant is widespread in North America, and has a long history of human use! (Spoiler though, it is poisonous.)

Recognizing the plant

If the post about magnolia got you excited about plant taxonomy, then I’ll tell you that this plant is a Eudicot. One of the first hints is that the veins in the leaves form a net, rather than being parallel lines as in most Monocots. You can also see that the flower parts are in multiples of five. This flower actually doesn’t have petals at all, and the white parts around the outside are sepals, which turn pink and then bright fuchsia as the fruit develops. There are ten stamens and ten carpels, which lead to ten seeds in the berry, giving it a pumpkin shape before it is ripe and after it is dried out.

I love how the racemes turn from white to pink as the fruit ripens, and many leaves die off to reveal bright pink stems, acting like a neon sign to tell the birds that the berry buffet is open for business. The local mockingbirds like to sit and sing in my neighbor’s tree, so I’m excited to see them drop down to this plant for a sweet treat.

Uses

As I mentioned, most parts of this plant are toxic to humans. It might just give you diarrhea but it’s also entirely possible to die from consuming it (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai 2023). Of course, dosage makes the difference between poison and medicine, so under the direction of an expert this plant can be used medicinally. My grandfather’s copy of Using Wild and Wayside Plants (Coon 1980) simply lists it as “cathartic”, which I learned means “laxative” (well now that word is ruined for me). In Stalking the Wild Asparagus it is also listed as narcotic and slow-acting emetic (Gibbons 1962). I have also seen claims that it can be used for rheumatism and sprains (Witchwood 2019).

Pokeweed it also recognized by modern science for having a unique ribosome-inactivating protein with anti-viral properties (Domashevskiy and Goss 2015). When the plant is infected with a virus, the protein is released to prevent the plant’s own cells from replicating the virus. This protein has been investigated both as an antiviral and anti-cancer drug (Domashevskiy and Goss 2015; New York Botanical Gardens 2017). Ribosomes make all of the proteins in our cells, so to prevent them from working is very toxic (or “cytotoxic”, meaning toxic to cells). The idea behind using this is a drug is akin to chemotherapy, where it’s a bit more toxic to the cancer than it is to the rest of you. There has been some research to engineer the ribosome-inactivating protein to be attached to an antibody targeting tumor cells, which helps to concentrate the engineered protein into those cells and away from the rest of the body (Lu et al. 2020). Anyway there don’t seem to be many recent scientific publications on using the pokeweed ribosome-inactivating protein as a therapeutic, and the two fairly recent once that I cited in this paragraph were published by MDPI, which has a reputation for low standards. Use of this protein as an anti-viral or anti-cancer drug must either not be very promising or not very profitable! In any event, if you boiled pokeweed leaves to remove their toxins, you would denature the protein in the process, so don’t go munching on pokeweed to try to cure cancer.

While no grocery store is going to stock a deadly plant in its produce section, if you do a quick Google search you will find that young pokeweed shoots have been traditionally consumed in the US for quite a long time. The trick is to only harvest very young shoots (i.e. 4-6 inches), and to boil them very thoroughly with multiple changes of water to remove the toxins (Coon 1980; New York Botanical Gardens 2017). The boiled shoots are called “poke sallet” or “poke salad”, as made famous in the swamp rock song “Polk Salad Annie”. Stalking the Wild Asparagus has lots of advice for preparing pokeweed shoots boiled, fried, preserved, or pickled, and also suggests keeping the tubers in the cellar over the winter in order to harvest shoots as they emerge (Gibbons 1962). I’m not feeling quite adventurous enough to try eating it, plus I just don’t have quite that much of it growing in my yard.

The other big use of this plant is the pigment from the berries. And as I’ll describe below, holy cow do they have a lot of pigment. In the genus name Phytolacca, “phyto” means “plant”, and “lacca” refers to a type of insect historically used to make red dye (Coombes 2002). The type of pigment made by pokeweed is called “betalain”, and is only produced by plants in the order Caryophyllalaes, of which pokeweed is a member (New York Botanical Gardens 2017), and some mushroom species. The betalain made by pokeweed has a rich fuschia to purple color. Betalain pigments are also found in pokeweed relatives such as beet, amaranth, cacti including dragonfruit, and swiss chard (Sadowska-Bartosz and Bartosz 2021). (“Beta” is Latin for “beet”, hence the name “betalian.”) Juice from pokeweed berries can be combined with vinegar and used to dye wool (Coon 1980). I have also read a recommendation to use it as a food dye for frosting and candy since only the seeds are poisonous and not the juice (Coon 1980), but I don’t think I’d want to risk making pink unicorn cupcakes for my daughter and then cause an entire birthday party of small children and their parents to have… a catharsis. Beet juice can do just fine as a natural red food dye. Perhaps most importantly, the berries can be used to make ink, and many letters written during the American Civil War were written in pokeweed ink (New York Botanical Gardens 2017; Witchwood 2019; Wigington 2019).

Pokeweed has been used in various cultural practices. In late nineteenth and early twentieth century North Carolina, the twelfth day after Christmas was known as “Old Christmas”, and the house would be decorated with pokeweed stalks early in the morning (Parsons 1917). In modern witchcraft it can be used for purposes such as courage, protection, purging, and cleansing, particularly by using the ink to write a spell on paper, or for the more adventurous, consuming the plant to induce vomiting and diarrhea (Witchwood 2019; J 2020; Wigington 2019). Native Americans used the berries to paint their horses, in addition to using the plant medicinally (Witchwood 2019).

One last cool science tidbit about pokeweed: the betalain pigment from the berries has been used to create solar power cells (New York Botanical Gardens 2017; Güzel et al. 2018)!

My inky adventure

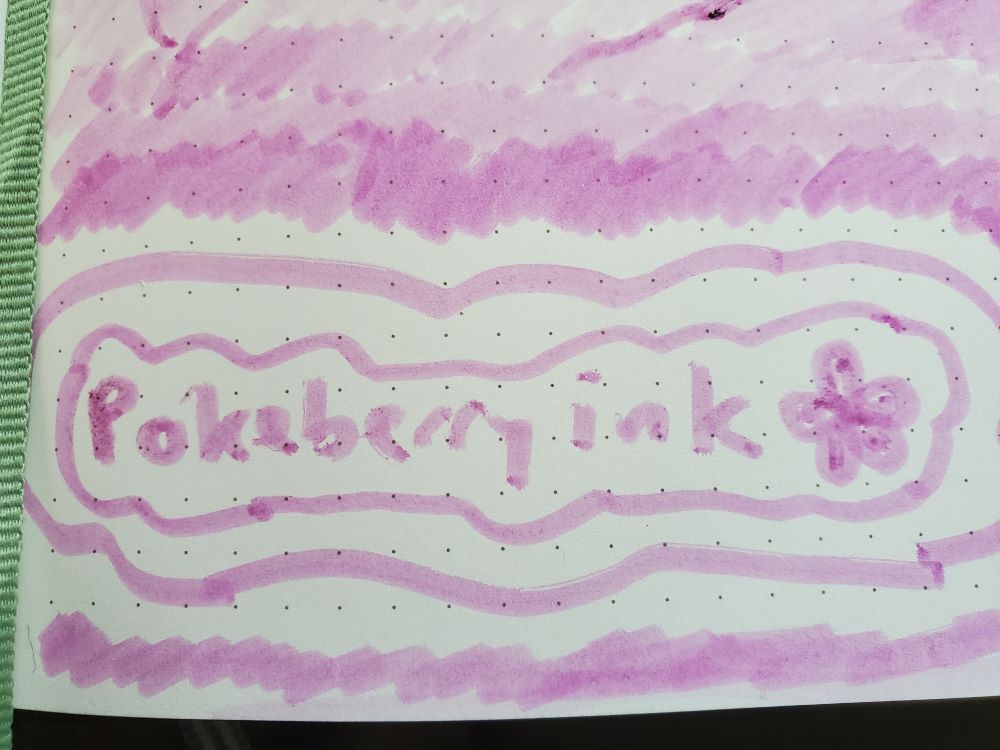

Intrigued by the notion that I had a native plant in my yard that could be used for ink, I put three ripe berries into a Ziploc bag, squished them up, and dipped in my clear Tombow marker. I had enough ink that I could have colored a whole page.

A week later I gathered some berries for a friend on my OBOD seed group who was interested, then I waited another week to gather some more for my own use. The ink recipes I have found online suggest using two cups of berries (Witchwood 2019; Wigington 2019), but I wouldn’t get that many unless I repeatedly stripped the stalks in my backyard bare, grabbing ripe berries every day before the birds got them. Based on my experience crushing up three berries I didn’t expect to be needing nearly that much over the next year. I’d much rather let the birds continue to enjoy them. So, when I gathered them for my friend I took only about half of what was ripe, then when I gathered them for myself I noticed that the birds had been ignoring the dried up berries, so I gathered some of those.

I made a couple of attempts at ink, the first soaking the dried berries in rubbing alcohol, then a separate batch of dried berries in water and vinegar. The ones in rubbing alcohol oxidized and turned brown pretty quickly over the course of about a week. Neither gave me the intense concentration of pigment that I got from fresh berries, so I may wait for a future date when I have a much larger crop of fresh berries to try to make ink. I’ll plan to update this page if I am successful!

Spirituality

I find it interesting that Marble Crow reported almost pulling up pokeweed before she knew what it was, but then having some urge to see what it grew into (J 2020). While my husband was planting his dogwood, he yanked up a young pokeweed shoot that was a couple yards away, and I commented that I didn’t know why that was necessary. At the time, I also hadn’t learned anything about this plant. Of course, being a perennial it came right back with a vengeance. It makes sense that to a modern gardener’s intuition, it hits all the buttons of a weed that needs to be removed, with its fleshy stems and fast growth. (Indeed, it is an invasive species on other parts of the world (Bentley et al. 2015).) But perhaps digging into a more primal intuition, we know that it is something important and useful. I spent some time meditating with the smaller, greener pokeweed plant in my yard, and while I’m not sure I have anything especially profound to report, I did feel like its presence provided some sort of protection for this plot of land.

Pokeweed is also a reminder that many entities in nature can be helpful or harmful, and all deserve respect when working with them. As a child I loved to play in the ocean with a body board. I remember many times that it felt like a wave picked me right up, carrying me to shore as I screamed with delight. The same waves could pull me under and beat the crap out of me. Likewise, this plant can be used for food or medicine, but can also kill you. It’s important to know what you’re dealing with before diving right in.

Anyway, since I am trying to build some creative skills while working through my Bardic grade, here’s a sketch of a small pokeweed plant. A month and a half after I drew the picture, the same plant had a few ripe berries, and I used one to color it.