Overview of the palm family

You don’t have to go very far in Florida to find palm trees! My daughter even made a game of spotting them from the car when she was two years old. All palm trees belong to one family, the Arecaceae. Every plant family must be named after one genus within that family1, so the palm family is named for the areca palm, which grows in the tropical Pacific. Then the “ceae” at the end just means “it looks like this thing”. Note that cycads like coontie (Zamia integrifolia) and sago (Cycas spp.) may be sold next to the palms in your local nursery, but are actually more closely related to pine trees than they are to palm trees. All true palms are monocots, putting them in the same major clade with grasses, lilies, orchids, and arums. Banana trees (Musa spp.) and yucca trees (Yucca spp.) are also monocots and somewhat resemble palm trees, although they are not palms. Other than that, not many monocots can grow into trees since the structure of their vasculature prevents their stems from getting wider as they grow, which is also why palm trees don’t form tree rings. Palms have been widespread for about 85 million years, since the Cretaceous era (Matsunaga and Smith 2021). You may already associate artwork of dinosaurs with palm trees, although if you see art of Jurassic or Triassic dinosaurs, flowering plants did not yet exist then and so the artist may have been trying to depict cycads or tree ferns.

You can find more species of palm in south Florida than in the rest of the state, but for this blog post I am going to stick to species around me in central Florida, starting with some non-native trees used in landscaping and the moving on to the natives.

Date palm (Phoenix dactylifera)

When I saw that the genus of date palm was the name of a mythical bird, I had to look into the etymology! “Phoenix” is actually the Greek word for date palm, and the word has been used for palms and mythical fire birds all the way back into ancient times (Noujeim n.d.). No one is quite sure why, but it may be because both date palms and crimson dye were associated with Phoenicieans. Still, I like to look at the leaves and imagine them to be enormous tail feathers. A few other Phoenix species besides P. dactylifera are common landscaping plants in Florida (UF/IFAS Extension n.d.a). Just looking at the ones around me I can see a lot of variation in trunk width, the length of the leaflets and the overall curvature of the leaf.

Date palms are native to the Middle East, where they have long been cultivated for their fruit. Believe it or not, it doesn’t get hot enough in Florida for most varieties to bear fruit, and for those that do, the fruit rots from the humidity. So they are a popular ornamental here, but don’t stand much chance of naturalizing. As someone with ancestors from the Middle East, this tree represents a connection for me to that past, as I will describe further below.

Queen palm (Syagrus romanzoffiana)

The queen palm has a pinnate leaf shape like the date palm, although the leaflets are a bit more flexible and so don’t tend to line up perfectly with each other like they do in date palm. You can also tell it apart from date palm by the smooth trunk. This species is native to South America, where it is common and widespread. A single fruit cluster can weigh 100 pounds, so people who plant this tree may have a lot of cleaning up to do (Broschat 2018b)! Of the four genera that I discuss here (Phoenix, Syagrus, Sabal, and Serenoa), Syagrus is the only one not in the Coryphoideae subfamily, making it the most distantly related, diverging from the rest back in the Cretacious in the early days of the palm family.

Cabbage palm (Sabal palmetto)

Cabbage palm is native to Florida and the coastal southeast US. It is incredibly common where I am, both in the wild and as a landscape planting. From walking around looking at it there seems to be a good amount of genetic diversity for leaf size and shape as well as the appearance of the trunk. The leaves are fan-shaped rather than feather-shaped, making it look pretty different from date palm and queen palm. You can find it as a classic lollipop-shaped palm tree, but also growing in the forest understory, with a short, squat trunk and huge leaves.

This species is called “cabbage” palm because of the edible growing tip, AKA heart of palm (Broschat 2018a). A few other species are used to make heart of palm. Harvesting from the wild is generally considered unsustainable, especially since harvesting the heart kills the entire stem, which usually means the entire tree. A different species of palm, Bactris gasipaes, is cultivated for production of heart of palm since it can produce multiple stems and thus survive the harvesting process. So, if you eat heart of palm, please be mindful of how it was produced. In addition to its use for food, cabbage palm has been traditionally used for building and cordage making (UF/IFAS Extension n.d.b).

Where I am in the dry scrub and pinelands, there is another species called Sabal etonia (scrub palmetto) that looks a lot like S. palmetto but never grows a tall trunk (UF/IFAS Extension n.d.b; Fox and Andreu 2019). If you just see a bunch of leaves poking out of the ground it could be either species, but if it is flowering without having a visible trunk, it is definitely S. etonia. This and other short species are where we get the word “palmetto”, from the first Spanish explorers noting all the little “palmitos” in Florida (Fox and Andreu 2019).

Fossils found in Texas indicate that the Sabal genus is about 75 million years old (Manchester, Lehman, and Wheeler 2010; Matsunaga and Smith 2021)! There is even evidence that dinosaurs were eating the fruit. To put this age in context the oldest oak (genus Quercus) fossils are 35 million years old, the oldest pine (genus Pinus) fossils are 140 million years old, and the oldest Homo (humans and close ancestors) fossils are 2 million years old. Despite this incredible age, Sabal species today are only found in the southeast US, Caribbean, Bermuda, and Central America (Heyduk et al. 2016).

Saw palmetto (Serenoa repens)

This species is also pretty common in the dry pine forest and scrub near me; I would say that about 2/3 of the palms that I see are Sabal etonia and the other 1/3 are Serenoa repens. Unlike either Sabal species mentioned in this post, saw palmetto grows a trunk that lays prostrate on the ground. I’ll talk more in section on leaf shape about how to tell Sabal and Serenoa apart. Lucky for me a nice blog post on saw palmetto came out from the University of Florida Extension while I was working on this blog post (Milligan 2024). This species is very fire tolerant, so one could use it as a symbol of the element fire, rebirth, and resiliency. Extract from its fruits has been used to treat enlarged prostate, although recent meta analysis of the literature suggests that it doesn’t actually work (Franco et al. 2023). The large blooms that it produces in the late spring attract hundreds of insect species to feast and mate in their own little Beltane celebration, and the fruit is eaten in the late summer and fall by many mammals and birds as well as gopher tortoises (Milligan 2024), making it a “foundation species” that is crucial for its ecosystem (Takahashi et al. 2011). Despite the abundant flowering of saw palmetto, DNA evidence indicates that it mostly propagates vegetatively by resprouting from the stem, and that a single plant can live for thousands of years in this way (Takahashi et al. 2011).

Leaf shape in palms

Nearly all palms have compound leaves, which means the leaf is divided into leaflets. The opposite of compound, when the leaf is not divided up is called simple (or entire). Most monocots have simple leaves, so palms are an exception. Some good examples of dicots with compound leaves are roses, blackberries, poison ivy, and clover.

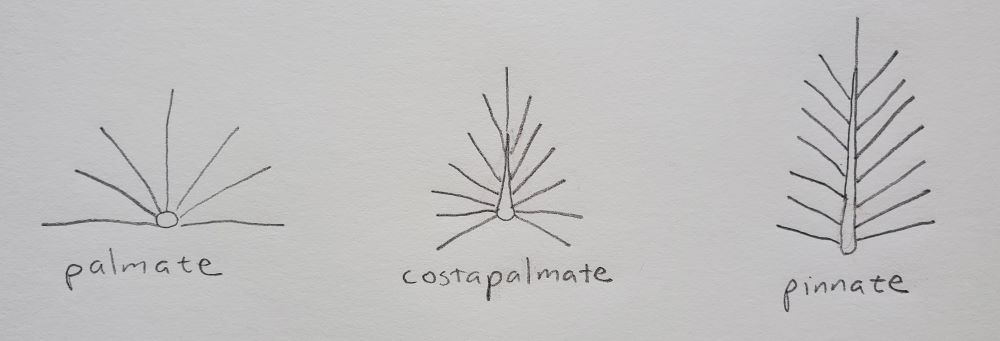

Compound leaves are usually classified as either palmate, in which all the leaflets radiate out from one central point, or pinnate, in which they come off in pairs perpendicular to a central axis. Saw palmetto is an excellent example of palmate leaves, and date palm is an excellent example of pinnate leaves. However, nature laughs any time we try to classify something as a binary, and so cabbage palm has a special intermediate shape called costapalmate, which starts out palmate near the base of the leaf but then becomes more pinnate closer to the tip. Walking around looking at cabbage palm leaves, I noticed that the attachment of the leaflets to each other in this costapalmate shape causes the leaf to fold into a three-dimensional structure. The costapalmate leaf shape is very ancient, with fossils dating 50 million and 75 million years found in Wyoming and Texas respectively (University of Oklahoma Libraries n.d.; Manchester, Lehman, and Wheeler 2010)!

I started paying attention to leaf shape because I wanted to be able tell cabbage palm and saw palmetto apart when they are just a bunch of leaves poking out of the ground. I found a nice article that illustrated the differences in leaf shape very well, with Serenoa having palmate leaves and Sabal having costapalmate leaves (Belanger 2009). I used to think that all the palmettos growing in my area were saw palmetto, so I was pretty tickled to be able to tell them apart all of a sudden once I knew what to pay attention to. In the course of working on this blog post I went from thinking all the palmettos were Serenoa repens to thinking many of them were Sabal palmetto to finally realizing they were Sabal etonia, so it was a delightful and nerdy journey for me. And of course, date palm and queen palm have a pinnate leaf shape, which makes them easy to tell apart from Sabal and Serenoa.

Why did these different leaf shapes evolve? There isn’t a clear answer, but one study of the palm family found that pinnate leaves are associated with taller trees and more humid environments as compared to palmate, costapalmate, and simple leaves (Torres Jiménez et al. 2023). And more broadly across the plant kingdom, leaves that are compound or very narrow are more tolerant of hot, dry conditions than wide, simple leaves are, because there is more surface area for dissipating heat when the stomata (microscopic pores) are closed and transpiration is no longer cooling the leaf. The compound leaves of a palm might also help reduce its wind drag (important here during hurricane season!) and maximize light capture given that palms don’t have any branches.

Leaf bases

One common trait of monocots is that the leaf base wraps protectively around the stem. Think of the many layers of an onion; those are all leaf bases, and the stem is the tiny part at the bottom where they all attach. Or grass, where the bottom part of the leaf forms a cylindrical sheath. So we see this in palms as well, with the leaf bases forming stacked or criscrossed patterns that remain after the main part of the dead leaf has broken off. Sometimes the dead leaf bases fall off to reveal a bare trunk. It is pretty common to see cabbage palm with and without the leaf bases, which is likely due to genetic variation within the species (Broschat 2018a). Here are two trees that I found at the Florida Sheriff’s Youth Ranch during the Florida Pagan Gathering. Same species but very different appearance! I felt very drawn to the one with the leaf bases still attached, and spent a lot of time sitting with it.

If you look at the other various species described in this post you can see differences in how the leaf base attaches to the stem. In queen palm, the leaf bases are very broad, extending about a third of the way around the trunk, whereas in the other species the leaf bases are much narrower. In cabbage palm the leaf bases attach to the trunk in a criscrossed manner, whereas in saw palmetto and date palm they are more stacked. One of the other defining characteristics of Sabal is that the leaf bases split in half where they attach to the trunk.

When palm leaf bases remain attached to the trunk, they provide habitat for ferns, lizards, tree frogs, and insects (City of Sanibel Vegitation Commitee n.d.; Belanger 2009). I love all the life that comes from these tiny little spaces.

Connecting to my ancestry

Out in the dry scrub near my home I have a favorite meditation spot. Feet in the sand, sitting before a saw palmetto, hot sun on my face, I am transported back through my Syrian ancestry to the ancient city of Palmyra. Built on a desert oasis, it was a bustling, cosmopolitan trade hub two millenia ago, although the city itself was at least two millenia older than that. Known in Arabic as Tadmur, its name may have originally meant knowledge, love, and wonder, although ultimately the name stuck because the city was full of palm trees. To this day, Palmyra is a major region of date palm cultivation in Syria (al-Garib 2023). Dates are an ancient and sacred food in the Middle East and North Africa, with human consumption going back to the stone age (Begum 2023). Today, dates are a central food at weddings and festivals, and are used to break fast during Ramadan. I imagine the alchemy of date palms must have made them sacred far into prehistory; their requirement of an underground water source, as well as extreme, dry heat for producing fruit, combining the elements of water and fire to create a fruit that is not only delicious, but calorie-dense and easy to store and transport. Several other palm species in the Coryphoideae subfamily grow in the Middle East, including some with costapalmate leaves and tall trunks like cabbage palm, and some that are more shrub-like and have palmate leaves like saw palmetto, and all of these have historically been used for construction, fiber, basket making, and fuel (Thomas 2013).

A great street, lined by colonnades, runs through Palmyra, leading past bath houses and a theater, up to the great temple of the god Bel, the supreme god of the Palmyrenes, and his acolytes Yarhibol, the ancient sun god of the oasis, and Aglibol, the moon god. Many other gods are worshiped here, reflecting the diversity in the city, and as we walk down the street we pass the temples of the Mesopotamian god Nabu and the Canaanite god Baalshamin. But I am not here to visit these. I am a nomadic Arab, in the city to visit and trade for the season before I return to my tribe to help tend our herds. On the other end of the street, about as far as you can possibly get from the temple of Bel, is a temple to the ancient mother goddess of my people, Al-Lat. On the temple grounds I chat with other Arabs about our disdain for city life and for organized government, but when I am away I do find myself quietly missing this temple. On the temple wall is a relief, twice as tall as a person, of a fearsome lion guarding a meek gazelle, with an inscription promising protection to all who can put their petty differences aside and make peace. Inside is a statue of Al-Lat, in the style of Greek statues of Athena. We pray to Al-Lat when we need help finding love, conceiving a child, or getting through a famine. My feral desert goddess, the heat of the sun is her love and her wrath. A slender figure walking behind the veil, running her fingers across the fabric of reality. This goddess is so important that hundreds of years later when the Quran is written, there is a controversial passage in which Muhammad changes his mind about whether it is acceptable to continue to worship her and her two sisters. One of her symbols is the crescent moon. Perhaps you know her?

The Temple of Al-Lat in Palmyra stood for two centuries, seeing reign of the badass Queen Zenobia, before being destroyed under the rule of Christian Rome. The Temples of Bel and Baalshamin were converted to a Christian churches, and then the Temple of Bel to a mosque, over the centuries, before being destroyed using dynamite by the Islamic State in 2015 during its occupation of Palmyra. Khaled al-Asaad, 83-year-old head of antiquities in Palmyra, refused to evacuate before the invasion and refused to give up the location of artifacts he had hidden despite months of torture at the hands of the Islamic State. Legend says that he refused to kneel for his beheading in 2015, saying “The palm of Palmyra dies standing.” The destruction of these temples and the museum is so painful to imagine, but more than that my heart breaks for the poor angry kids who got brainwashed and recruited into this. Four hundred of them were killed when the Syrian army retook Palmyra, leaving behind bunkers and sandbags amidst the ancient colonnades and crypts. May the lion of Al-Lat protect all who work for peace.

Further reading on Palmyra and Al-lat: (Hoyland 2001; Saab 2020; “Greco-Roman Palmyra: The Gods of Palmyra” n.d.), plus see a 3D model of the Temple of Al-Lat; a video of the archaeological site, complete with date palms; and a map of Palmyra. Since encountering this goddess I have felt her presence most closely when praying for peace. She wants peace in the Middle East, and I hope that she can also help me to be a vessel of peace in my own country, where I have to raise a child while wondering how many of my neighbors are stockpiling weapons and ammunition in eager anticipation of a civil war.

References

Footnotes

Graminae and Compositae were a couple major exceptions that persisted for a long time before being changed to Poaceae and Asteraceae, respectively.↩︎