Local plants in the Fabaceae

Right after Lughnasadh (August 1), this little bushy plant burst into bloom with clusters of tiny purple flowers. A group of wasps was working diligently at collecting nectar and pollen.

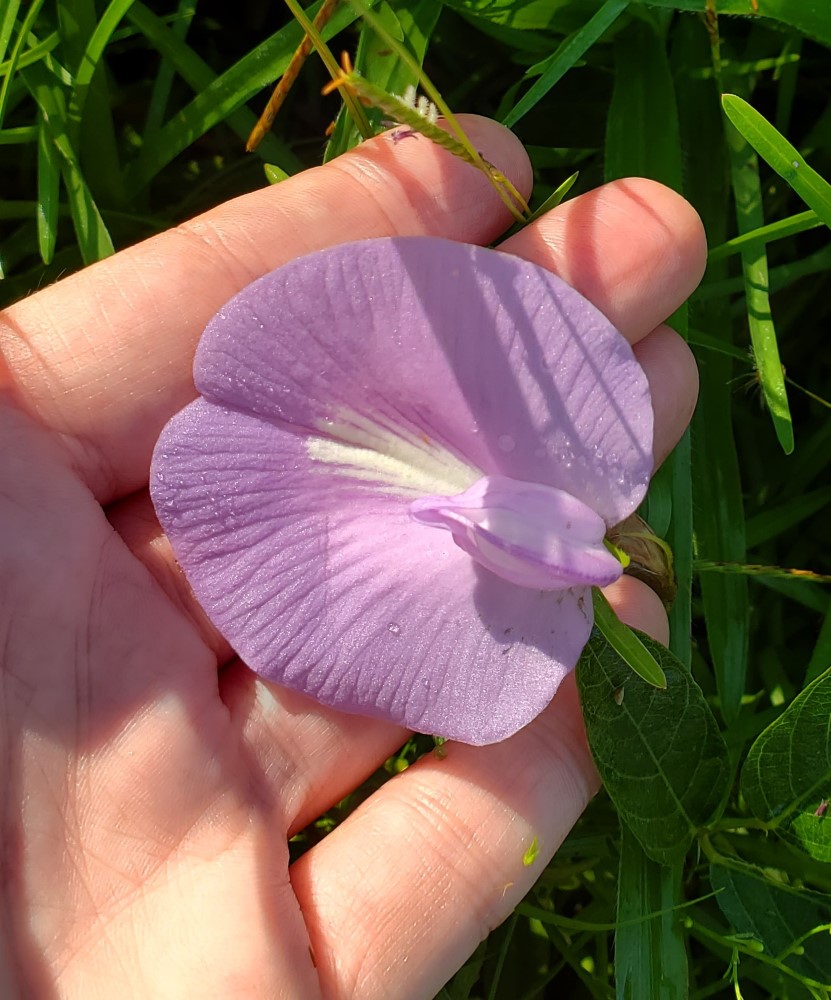

Here’s a much larger purple flower on the same day in the same backyard, growing off of some vines.

And a different plant in my neighbor’s front yard a couple days later:

And a vine in my backyard a couple weeks after that:

And a tiny herb growing in the grass the next day:

And here are a couple of the same plants going to seed around Alban Elfed (the autumn equinox).

Between Alban Elfed and Samhain, I saw quite a lot of this plant growing into small flowering shrubs.

Right after Samhain I was going for a walk on the Cross Florida Greenway and ran into a woman who was happy to see me carrying some trash off the trail. She pointed out these flowers to me and introduced them as “showy rattlebox”. It was a very awen-y moment and inspired me to try to finally finish this post. Sometimes the forest spirits we meet are humans. Of course, I later looked it up and discovered that it is a toxic introduced plant from Asia and a problematic agricultural weed, despite her suggesting that I take some home to plant in my yard. So a mischievous spirit?

Traits of the Fabaceae family

If you are starting to guess that these are related to the bean and pea plants you have growing in your garden, congratulations on your botanical sense! All of these plants are in the Fabaceae (pea) family, which is huge and diverse. Family is the next taxonomic rank up from genus, although often botanists have found it necessary to squeeze in “subfamilies” and “tribes” to better subdivide families by the evolutionary relationships within them. As so wonderfully described in Thomas Elpel’s Botany in a Day, once you learn plant families you will start to recognize plants much more easily and intuitively (Elpel 2006). The next rank up, order, usually contains too diverse a group of plants for an amateur to easily notice how they are all related. But families have patterns that are easy to recognize, especially when it comes to flower shape. Obviously, knowing what family a plant is in really helps to narrow it down for identification. But what’s better is that even without knowing the genus, you can make some educated guesses about whether a plant is edible or poisonous and what its medicinal properties might be. Elpel has also graciously put the Fabaceae section of his book online and added lots of photos (with links to more), so I recommend giving it a look.

What are some traits that you can use to identify the Fabaceae? The flowers are “irregular”, meaning they don’t have radial symmetry like the quintessential flower that one might doodle. There are five petals, but they are specialized into different shapes, usually with one of them making a banner, two wings, and two fused into a keel. The seeds are always in pods, like peas or beans. The leaves are usually compound, meaning the leaf is divided into multiple leaflets. Often there are three leaflets, but there can be many more than that in a pinnate arrangement, with one at the end and then multiple pairs along an axis. All the pictures I have put here are of herbs and vines, but there are also Fabaceae that grow as shrubs and trees.

One quick note on a plant that is not in the Fabaceae. Oxalis (wood sorrel) is often mistaken for clover (Trifolium) because it has three leaflets. You can tell the difference because the leaflets of Oxalis are heart-shaped, whereas the leaflets of American clover species are round. And if you see Oxalis flowering, the flowers have a very regular appearance with five identical petals, clearly not like pea flowers. The confusion probably arises because both Oxalis and Trifolium can be called “shamrocks”.

The Fabaceae falls within the Eudicots clade. All members of the Fabaceae are legumes, and all legumes are members of the Fabaceae. These plants are famous for their symbiotic relationship with nitrogen-fixing bacteria. It is now known that all land plants have symbiotic relationships with bacteria and fungi, but the Fabaceae were one of the first to be discovered since the roots form macroscopic nodules where the bacteria grow. The bacteria take gaseous nitrogen out of the air and convert it to ammonia, which can be used by the plant to build amino acids and other compounds that it needs. If grass grows poorly on your lawn and clover (a legume) takes over, it probably means the soil is nitrogen-depleted, giving the clover a big advantage since it can provide its own nitrogen. After a few years of clover putting nitrogen back into the soil, other plants will move back in. This is the trick behind the corn-corn-soy crop rotation used so widely in the Midwest; corn takes nitrogen out of the soil and soy puts it back in. (Biodiversity is good and so industrial agriculture has adopted one (1) aspect of biodiversity. Industrial agriculture isn’t all bad since high yields mean less land is needed, but that’s another post. If we all stopped eating meat we wouldn’t need nearly so much land for agriculture, industrial or organic.)

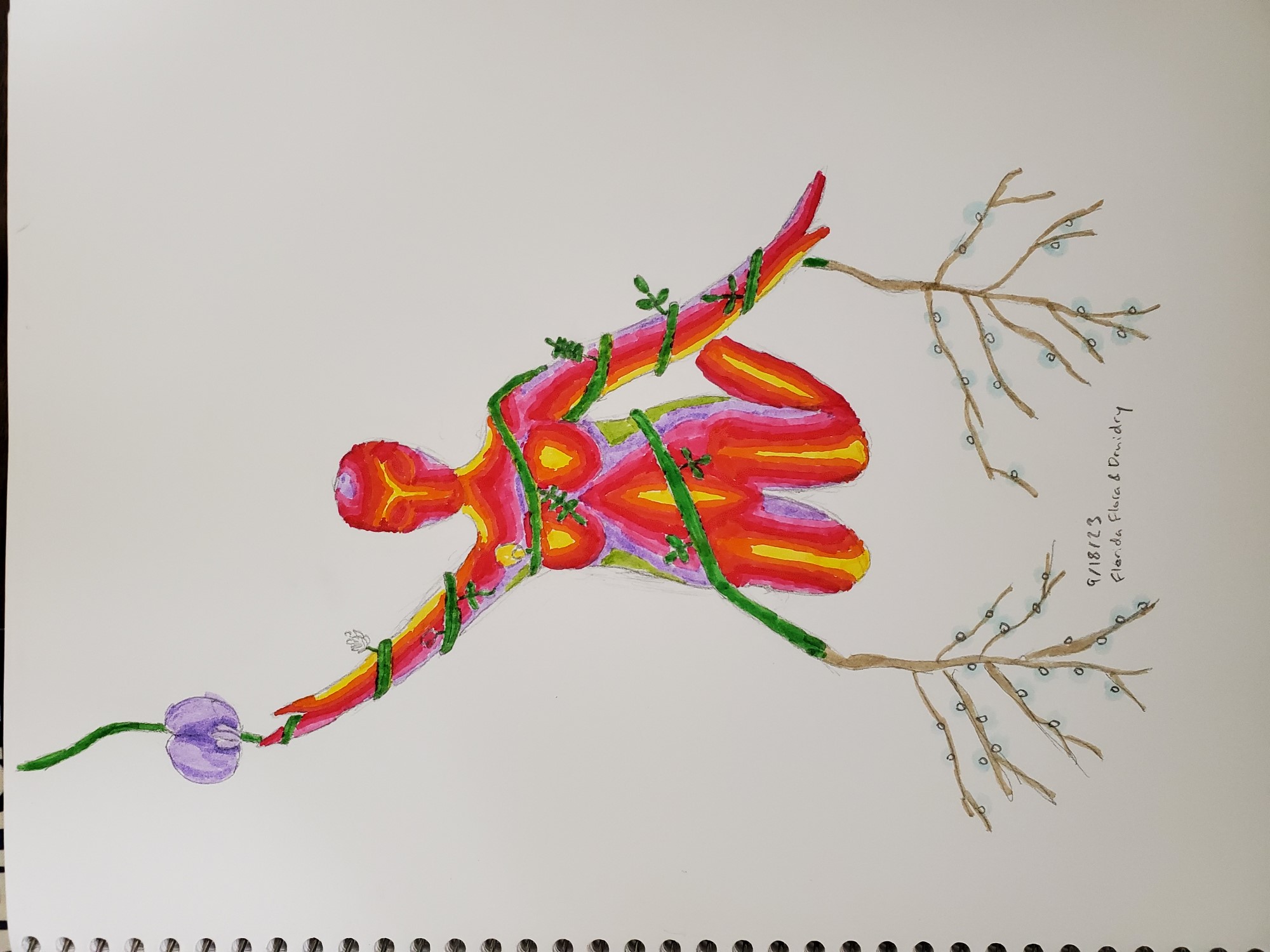

The feminine aspect

Many plants in the Fabaceae could be appropriate for honoring the feminine aspect, given the resemblance of the flowers to female genitalia. Charles Linnaeus wasn’t shy about naming one genus Clitoria, although he had to make it weird by naming one species Clitoria mariana after a woman he was courting (Benda 2015). I don’t think my husband would want me naming a plant after his junk. Anyway, NO to celebrating an individual person’s genitalia without their consent, but YES to celebrating the Goddess, sexuality, and femininity more broadly. You can also think of the Fabaceae as having a nurturing aspect, providing nitrogen for other plants as its leaves fall off and decompose.

A few days after Alban Elfed (the autumn equinox), the Centrosema virginianum (butterfly pea) in my yard was still in full bloom and I happened to see a bumble bee going from flower to flower collecting nectar. It certainly felt like a fertility rite, with the bee landing on the wide platform of the banner petal, then shoving its way into the tight pouch formed by the wing and keel petals. As it did so, the stamens were pushed out from the pouch as if by a lever, scraping against the bee’s back to deposit pollen. On Youtube there’s a nice educational video of bumble bees pollinating a different Centrosema species.

Please enjoy some Fabaceae-inspired Goddess art. Until next time!